[Hey, hi! I’d love for you to toss me a couple of bucks each month. It’s easy to back me up at $2, $5, or $20 a month! Surely I’m worth a little bit of cash, you think?]

V3, I2

I don’t understand poetry.

That’s a heck of a thing for me to say, since I consider myself a poet and have written quite a few poems1. Still, it’s true. I don’t get poetry at all. Worse, I don’t understand how to write poetry. Let me explain.

Last year, I meant to write a quartet of poems for Advent — one for each week on the theme for that week. Then, I’d write one for Christmas Day that would bring all the themes together. I got two poems in and…things happened. Flood things2. Let’s say the spirit of the season was not exactly deep in my heart. It sure as heck wasn’t on my creative mind.

This year, I thought I’d give it another try, only this time, instead of relying on free verse, I’d choose a more formal structure for the poems. The sonnet form seemed pretty good to me, especially since “sonnet” comes from the Italian word for “song”. The only problem is that I don’t have a lick of formal training in poetry writing and only one semester of a poetry appreciation class from my time in community college3. Fortunately, I have the internet, so off I went to learn about the sonnet — its suitability for the themes of Advent and, more importantly, how to write one.

Turns out, the sonnet structure is pretty simply at first glance. Write a poem of 14 lines, each in iambic pentameter4, with a particular rhyme scheme, depending on how you divide up the lines. A Petrarchan sonnet is divided into sections of 8 lines followed by 6 lines. A Shakespearean sonnet is made of three 4-line sections followed by a two-line section. Regardless of the type, a sonnet has to have a “turn”, called a volta, that reverses the poem in some way. For a Petrarchan sonnet, the turn happens at the beginning of the 6-line section (on line 9); in the Shakespearean sonnet, it happens on line 13. Each type of sonnet has its own specific rhyme scheme as well. I won’t bore you with those details, but you can see them in action if you like. Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “Sonnet 43” is Petrarchan. Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 18” is, well, you know5.

Turns out, sonnets dealt heavily in subjects of love and adoration, which suits my purposes just fine. After all, what is the heart of the Christmas story but love?

Easy-peasy, chicken-squeezy, right? I have a solid form for the poems I want to right and a good structure for them as well. What could go wrong?

As it happens, the sonnet isn’t as well-defined as I let on. See, poets decided they didn’t have to stick to the rules of construction. Even Shakespeare broke the sonnet rules a few times. A couple of his sonnets weren’t in iambic pentameter. Other poets decided to stretch sonnets to 16 lines. Some decided the meter didn’t matter at all. Others threw out the rhyme schemes and even the notion that a sonnet needed to rhyme at all. In fact, you can find plenty of sonnets out there that aren’t 14 lines, don’t rhyme, and don’t have an established meter.

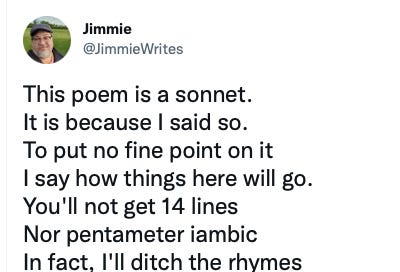

I find this incredibly frustrating. What, exactly, is the point of having a sonnet form when a poet can write any old thing, call it a sonnet, and have everyone agree? If “sonnets” written by Gerard Manley Hopkins6, can limp along without a particular metrical rhythm, what's the point of requiring imabic pentameter? Once you decide that requirement isn't necessary, why have any of the others? Once you've gotten to that point, any poem in the world can be a sonnet, if the poet says so. For example:

That isn’t a sonnet…or is it? I’d argue it’s not, even though I said it is. It meets none of the requirements so it’s not a sonnet.

But what if it met three of the requirements? What do we call Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 145”, which is written in iambic tetrameter7 but fits the definition in every other way? Clearly, it was "sonnet enough" to be included with all the others. Later on, poets decided to throw most of the sonnet rules to the winds without much hesitation and the poetry world has accepted all of it, as best I can tell. I took the matter to Twitter8 and the prevailing opinion is a sonnet is...whatever. One very smart poet (and I'm not being sarcastic in the least) said that the best definition of a sonnet is "something that can be recognized as a sonnet"; that is, a sonnet is whatever is sonnetish. I don't like that definition at all but, from the various comments and replies I've gotten since my first tweet asking for help, that seems to be the one that prevails. A sonnet is...*waves hands in a vaguely sonnetlike fashion*...whatever I say it is.

I suppose, then, that this could be a sestina.

And this is a limerick.

I don’t think that makes poetry “better”. It certainly won’t attract more people to poetry, as readers or writers. I can safely say I’m more confused about sonnets than I was when I knew almost nothing about them.

That’s not going to stop me, though. See, as an artist, I get to choose how I pursue my art. I also get to choose whose influences I accept and whose I refuse. At this point, I refuse “sonnets” that are only roughly sonnets. I will stick to the requirements and write the very best sonnets I can inside them. Later on, I might break a rule or two, but only when I've learned the rules very well9. For now, and for a good long while, I'm going to color inside the lines. That might sound boring, but I assure you I'm capable of some awfully good coloring.

There’s no inspiring call to action this week and no rousing inspirational thought. I figured a thousand words of my confusion will probably inspire you plenty. After all, there’s no way you could have spend more time in utter artistic confusion and frustration that I have the past couple of days. But if you have, know that I’m on your side. Tell me about it, okay? Put something in the comments or just hit reply and let me know what’s up.

A hundred and fifty, perhaps? Two hundred? I haven’t counted lately.

Short version, our apartment flooded in early December and we didn’t get back into it, after all the cleanup and repairs, until just a couple or three days before Christmas. I didn’t get a lot of writing done. It wasn’t a great time, though a good number of wonderful people jumped in and helped us with the huge financial issues that came up. They — some of you, in fact — were wonderful.

I don’t have a lick of formal training in any sort of creative writing. I don’t have a degree in anything either. I am (I think), a few credits away from an AA degree in Music, but the chance that I will finish that degree are roughly equal to the chances I’ll run a marathon.

Real quick. “Iambic” means each line is made up is iambs, which is two syllables where the second syllable gets the stress. “Da-DUM” is an iamb. “Pentameter” means you get five iambs in each line. If you had four, you’d have iambic tetrameter. Remember that one. You’ll see it later.

By the way, sonnets can have names. I just happened to pick examples that didn’t.

See, for example, “The Windhover”.

Told you.

My Twitter feed is both weird and cool. You may want to follow along. Or not. Honestly, I’m not pushing for either one.

Though when I do, I won’t call what I’ve done a sonnet. I choose to remain a snob about that!

Alternately, just make the art you want to make and let other people quibble later about labeling it. 🤔 Though I appreciate you wanting to adhere to a style as a challenge — just don't act too harshly as your own gatekeeper from the medium!

The call to action this week is SUPPORT JIMMIE ON PATREON! 💃🏻💃🏻💃🏻